- IDEA Public Schools

- Seeking civic literacy

- The Business of Giving

- The war on philanthropy

- Wild and wonderful

- Anonymous giving

- The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation

- Hillsdale College preserves donor intent

- Condoleezza Rice

- Tax-exempt churches

- Clarence Thomas speaks

- Where professors donate

IDEA PUBLIC SCHOOLS started with one campus in 2000 serving three grades in the Rio Grande Valley, and has become one of the most successful charter-school networks in America. IDEA currently serves 45,000 students at 79 campuses. Since 2007, 100 percent of its graduates have been accepted by colleges, with over 60 percent of them being the first generation in their family to get higher education.

Now, thanks to a multi-year $55 million philanthropic investment organized by the Scharbauer, Abell-Hanger, and Henry Foundations, IDEA will expand its footprint in the far west of Texas. The donors courted the proven operator with a request to open 14 campuses in the Midland-Odessa oil belt. All of the schools will eventually serve grades K-12, offering high-quality education, in a region that needs it, to as many as 10,000 students by 2030. The philanthropic partnership includes $16.5 million from the Permian Strategic Partnership, a collection of oil and gas companies.

IDEA has additional growth planned throughout Texas, Louisiana, and Florida. The Philanthropy Roundtable’s former K-12 education director Dan Fishman is IDEA’s in-house growth guru. Go, Dan!

ELSEWHERE IN ED, Nancy and Rich Kinder finished out 2019 by gifting $10 million to the University of Missouri to further bolster the Kinder Institute on Constitutional Democracy. The gift will be used to create two new degrees: a B.A. in Constitutional Democracy and an M.A. in Atlantic History and Politics. Money will also go toward the Kinder Institute Residential College, and a study-abroad partnership with Oxford’s Corpus Christi College.

Bernie Marcus is also investing in civics, announcing in January a $5 million gift to the Florida Education Foundation to fund a Florida Civics and Debate Initiative. The state effort aims to increase test scores on civic literacy and expand public-speaking programs to all public-school districts. “What Florida is doing to bring civics and debate to every student is very innovative and should be a model for the rest of the country,” commented Marcus.

HEARD AROUND TOWN… Philanthropy friend Denver Frederick interviews funders and charitable leaders on his WNYM public radio show “The Business of Giving.” (You can listen on line at denver-frederick.com.) Two favorite moments from recent episodes:

At Fidelity Charitable, we require that people be active grant makers. If they have not made a grant within three years, we will take 5 percent from their account…. If they don’t give the following year, we’ll sweep the whole account and then grant it out to charity on their behalf. Yet this is rarely required: We’re seeing, on average over the last decade, granting rates between 20 and 24 percent per year.

If someone decides to join a board of a nonprofit, they should take that board experience with every ounce of seriousness that they would take a corporate board experience—and I’m not sure they always do.

YOU MAY HAVE READ Karl Zinsmeister’s recent op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, “The War on Philanthropy.” Thank you for all your responses, and for sharing the piece so widely. Karl wrote a follow-up essay for RealClearPolitics, which we’ve printed below (and linked to here) for your enjoyment and concern.

In our current socialist moment, a veritable race is underway among journalists, academics, and politicians on the Left to outdo each other in thundering against business enterprise and personal wealth—and the private charitable action that flows from them.

The Model U.N. program now assigns “Toxic Charity” as a debate topic for schoolchildren. The New York Times editorial board has declared the famed Carnegie Libraries a “failure of public policy.” The “Top Big Picture Trend” of 2019, according to “Inside Philanthropy,” was today’s “Backlash Against Philanthropy.”

Names are being pried off of college buildings, museums are getting picketed, companies are facing boycotts. Long-time tax protections for charitable giving, churches, and charities are being attacked and proposed for repeal. Activists demand that government be given the right to appoint board members at nonprofits. Privacy protections for donors and charities are being eroded. No giver is safe.

A recent cover story in what’s left of Time magazine chirped excitedly that there are now more than 50,000 “dues-paying members” of the Democratic Socialists of America scattered across our fruited plain. The author is one of today’s most doted-upon critics of philanthropy, and he urges “solidarity” with “fresh” enemies of capitalism like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Bernie Sanders who will “put American business in a headlock.” He flames “plutes” (his sneer for “plutocrats” who are wealthier than him) in the hope that depersonalizing opponents (as was done with “kulaks” in the Soviet Union and “capitalist roaders” in China) makes it easier to discard them.

The deep odium for personal wealth and private problem-solving that is nursed by fashionable chatterers today often surges into view when businesspeople take up philanthropy. Jeff Bezos donates a million Australian dollars to fire recovery and the plute-smashers swing their axes. The $14 million Jack Ma puts up for a coronavirus vaccine is characterized as a pittance. David Rubenstein offers to renovate the Jefferson Memorial and other historical landmarks and gets attacked for being a private-equity villain. For crusading against malaria, Bill Gates is portrayed as a vainglorious megalomaniac.

As their real-world cure for “uncontrolled” philanthropy, these critics now openly call for confiscation of private wealth. “Say Bill Gates was actually taxed $100 billion,” Bernie Sanders tweeted recently. “We could end homelessness and provide safe drinking water to everyone in this country.”

The same journalist who wrote the recent Time cover story also authored a book savaging philanthropy. He attributes to donors every imaginable motive—vanity, cynical reputation laundering, undemocratic manipulation, drop-in-the-bucket cheapness—except altruism and good faith. For these fashionable arguments the work was anointed a “book of the year” by the Washington Post, the New York Times, and NPR.

Other critics make the same arguments. Philanthropic giving is “an undemocratic exercise of power” which should be wielded only by the state, says Stanford’s resident philanthropy academic. Even well-intentioned charitable efforts must be shut down, say the new activists, because they undercut the revenue and authority of the federal government. Powerful interests ranging from elite media to Democrats running for President insist that only government officials should be allowed to improve public welfare and reform society.

These ad hominem attacks and sweeping arguments are gradually poisoning the American public on philanthropy. More citizens every year are being convinced that private giving is just a racket run by moguls to aggrandize themselves. A “billionaire boys club” that numbs, deceives, and controls the rest of us. A means of deception and selfish string-pulling, rather than a way of helping the country or our fellow man. With this kind of rhetoric constantly in the media, cynicism about charity is swelling. Public views of nonprofits are at a nadir, and U.S. giving rates are tumbling.

This is deeply dangerous to the nation—because energetic private giving is one of America’s most valuable sources of ingenuity and social repair. Every single year, hundreds of billions of dollars ($428 billion last year), and hundreds of billions more in the value of volunteer time, pass willingly from generous helpers to others who are struggling. Our long tradition of improving society through the organic private action of civil society, mostly on a local level, has long been one of the distinguishing strengths of our country. Nothing like our charitable sector exists in any other land. It is one of America’s most unusual, and beautiful, anomalies.

And here’s the most troubling aspect of today’s noisy attacks on philanthropy: They are utterly false in their most fundamental claim. Our giving is not dominated by crafty tycoons. Emphatically not.

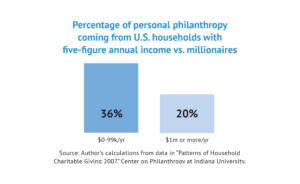

The fact is, only 20 percent of personal giving in the United States comes from the “plutocrats”—people making $1 million a year or more. Fully 80 percent comes from non-millionaires.

Indeed, the portion of individual philanthropy coming from households with modest annual incomes of five figures or less is close to twice as large as the portion coming from people in million-dollar households. See data nearby.

Portraying U.S. private giving as a Game of Plutes is not only dangerous and un-American. It is factually wrong.

WILD AND WONDERFUL West Virginia enacted the “Protect Our Right to Unite Act” to bolster donor privacy. ACLU West Virginia supported the legislation—its policy director told the West Virginia Gazette that “the groups that people join are none of the government’s business.” This bill “reaffirms the vital freedom of association.” We’ll be watching similar donor-privacy measures in other states.

MEANWHILE, CALIFORNIA’S LEGISLATURE is considering a law that would give the state Attorney General authority to collect donor information from donor-advised funds. The Alliance for Charitable Reform is working with allies in the state to protect donors of all stripes who prefer to remain anonymous.

THE ELI AND EDYTHE BROAD FOUNDATION made a $100 million year-end grant to Yale University to create a tuition-free master’s degree within the School of Management for superintendents and senior leaders in public schools. It’s the largest gift ever received by the Yale school, and creates successors to the Broad Academy and the Broad Residency—which, starting in the early 2000s, trained more than 850 leaders for the hard work of school reform, including over 70 who currently run state or municipal education systems, and many leaders of pioneering charter schools.

Big Idea: Treat Veterans as Resources, Not Recipients

Many veterans are well-equipped to take leadership roles in American society. FedEx and Walmart were founded by veterans. Political philosopher John Rawls was a veteran. Clint Eastwood, Paul Newman, Jimmy Stewart: all veterans. Of the 45 Americans who have served as President, 31 have been veterans.

But today we live in a disconnect between the victim culture that’s become so dominant and the reality of what veterans can contribute to American society. The policy apparatus in Washington, aided by sensational journalism, and also by parts of the charitable-industrial complex, have created a popular image of veterans centered on their alleged dysfunctions and brokenness and needs. Hard data show that veterans score significantly better than non-vet peers on most social indicators. Yet incessant questing after ever-larger entitlements and benefit payouts has created the impression that PTSD, homelessness, addiction, violence, and other maladies afflict most vets, and that veterans as a group must be viewed as clients rather than climbers.

Our veterans-service organizations once promoted veterans into civic leadership and used their associations to contribute broadly to American civil society—with many positive impacts still reverberating today. But the post-Vietnam focus on expanding benefits has now become all pervasive for these organizations, which too often act like rent-seeking interest groups. There is an outsized focus on what veterans require, rather than on their capabilities and what they can contribute.

Our country needs these storied organizations to recover their historic mandates in leadership development and community service. And we need entirely new nonprofits that help veterans lead, rather than training them to receive. The V.A. has become by far the largest and fastest-growing civilian bureaucracy in Washington, a bloat which is not sustainable. Far more importantly, veterans who truly need help are now choked in a system clogged with people who have been talked into the idea that they need to get onto the gravy train. Most vital of all, our fractured country needs the civic leadership and community glue that veterans can provide.

Veterans want this, too. Over the past decade, new vets organizations have sprung up to fill the self-improvement/civic-improvement roles abandoned by the legacy organizations. These new organizations emphasize work, community and public service, camaraderie, and personal development as mechanisms to help veterans thrive. They do almost no lobbying or political advocacy. Instead, they have attracted hundreds of thousands of younger vets by providing creative ways to help them connect with peers, thrive as individuals, and serve the country and local communities.

These organizations echo the words of Navy veteran John F. Kennedy: “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.” Each of these organizations, in various ways, promotes the idea that the best way to serve veterans is by asking something from them—encouraging them to become the leaders they are trained and tempered to be.

Commentators from across the political spectrum have bemoaned the challenges facing America: political polarization, a hollowing-out of civil society, ineffective public schools, loneliness and isolation, substance abuse, fatherlessness, cycles of poverty, declining knowledge of civics, and so forth. Imagine a country where veterans are equipped and sent out to change those things.

It is not a pipe dream. Many of those who have worn the uniform have courage, resiliency, capacities to inspire, and a patriotism that America can use today. We must stop treating these men and women as problems, and instead mobilize them to create solutions. Previous generations of veterans viewed individual success and civic leadership as natural civilian follow-ons to their armed service in behalf of American institutions and ideals.

Paradoxically, they discovered in the process that helping others thrive, and build character, and live safe lives is also a great path to personal satisfaction, healing, and growth. It is time to recover that vision for a new generation.

IN OUR FALL ISSUE we told you about a lawsuit filed by Hillsdale College against the University of Missouri alleging misuse of a $5 million endowment bequeathed by Sherlock Hibbs in 2002. A 1926 graduate of M.U., Hibbs stipulated that the gift be used to create six professorships filled by disciples of the Ludwig von Mises school of economics. In an unusual move, Hibbs named Hillsdale College as a contingent beneficiary, thus empowering Hillsdale to monitor whether Mizzou met the conditions of his gift. Hillsdale eventually sued Missouri for violating Hibbs’ donor intent. The gift terms provide that if the giver’s instructions are ignored, the funds spent to date (over $4 million) plus all funds remaining in the endowment (now over $9 million) should transfer to Hillsdale College.

In December 2019 the two institutions announced that they reached a settlement stipulating that Hillsdale will receive $4.6 million—half of the remaining endowment. The University of Missouri has promised to hold a symposium focused on Austrian economics at least every two years, while insisting that its spending has been “consistent with Hibbs’ intent.” Explaining why funds are being shifted, Hillsdale president Larry Arnn provides a different perspective: “Colleges—including the University of Missouri—are free to refuse gifts if they will not commit to fulfill the donor’s clear intent. What they are not free to do is to pledge one thing to a donor and then do another.”

Although naming a contingent beneficiary to monitor the original grantee (and take legal action if needed) is not common practice, in this case it successfully limited further erosion of a legacy. It may be an effective way in other circumstances to ensure that a trusted organization has standing in court to enforce a donor’s wishes years after a gift is made. —Joanne Florino

CONDOLEEZZA RICE will take the reins at the Hoover Institution come September. Rice states that “both the Hoover Institution and Stanford University are places that believe in the study and creation of ideas that define a free society. The nurturing of these ideas, the value of free inquiry, and the preservation of open dialogue are the backbone of democracy.” May it be so!

SEVERAL READERS have asked me what I think of the cover story in Christianity Today, “The Hidden Cost of Tax Exemption: Churches may someday lose their tax-exempt status. Would that be as bad as it sounds?” My short answer is “Yes. It is as bad as it sounds.” It’s not unusual to ask questions about the relationship between religious institutions and the state. It is highly unusual for a faith-focused publication to give air time to the opinion that, and I quote the author here, “It might not be such a bad thing to lose tax-exempt status.” This cavalier argument has caused consternation among people of faith and donors all across the country.

Just to clarify: religious institutions, and nonprofits writ large, are not tax exempt because the government deems them “good” enough to warrant a “subsidy.” That’s not the U.S. legal structure we operate in. Our freedom of association permits the creation, and funding, of institutions regardless of their adherence to government’s agenda of the hour. That’s why we call it the “third” or “independent” sector.

For an easily digested legal explanation, I highly recommend Alex Reid’s essay in the Almanac of American Philanthropy—his argument heavily shapes my own thinking. The essay is called “Why is Charitable Activity Tax-Protected? (Think Freedom, Not Finances).” Even if you don’t own an Almanac you can read the chapter here. And if you feel ready to bite somebody—I sympathize with you. I recommend a long walk, fiction, and kombucha.

A Clarence Thomas A CLARENCE THOMAS film is about to debut on PBS. Philanthropy asked our movie maven Madeline Fry to investigate and report back. Here’s what she found:

When Michael Pack heard that Clarence Thomas was tired of his narrative “being told by his enemies,” the producer decided to make a documentary about him. In Created Equal: Clarence Thomas in His Own Words, Pack let our nation’s most enigmatic justice speak for himself.

The two-hour film lets Thomas and his wife Virginia talk about everything from Thomas’s childhood to his political evolution and tenure at the Supreme Court. Over a six-month period, Thomas granted the filmmaker 30 hours

of interviews.

Dallas philanthropist Harlan Crow, who donated a few hundred thousand dollars to the project, says letting Thomas tell his own story was the right approach. “That was an unusual idea,” he says, which produced a “terrific” story.

Thomas tells his tale chronologically, beginning with his birth in Pin Point, Georgia, in 1948, years before the South was desegregated. He grew up with two siblings and a single mother, eventually going to live with his grandparents when he was seven. Given the way he talks about his grandfather it’s crystal clear why he titled his 2007 memoir (from which he reads throughout the documentary) My Grandfather’s Son. His grandfather taught him faith, a work ethic, and tough love.

Thomas’s politics, however, were in deep flux for many years. He describes how he evolved from an aspiring priest, to a Marxist and supporter of the Black Panthers, to a “lazy libertarian” at Yale. After he graduated with his law degree he accepted a job offer from Missouri Attorney General John Danforth with mixed feelings. It was a good position, but “the idea of working for a Republican was repulsive at best. I was a registered Democrat, I was left-wing, and as nice as he was, he was still a Republican.”

Thomas went on to work at Monsanto, where he chafed at the “golden handcuffs” of a “comfortable but unfulfilling life.” So in 1979, he returned to work for now-Senator John Danforth as a legislative aide. The next fall, he voted for Ronald Reagan. “I was distressed by the Democratic Party’s promises to legislate the problems of blacks out of existence,” Thomas says. Soon afterward, he was attacked in a newspaper article for voting Republican as a black man.

From then on, Thomas pivots his story to the tumult that has been his public life. The biggest draw of Created Equal is Thomas’s responses to the attacks that have dogged him for years, especially concerning his confirmation hearing. “One of the things you do in hearings,” Thomas quips, “is you have to sit there and look attentively at people you know have no idea what they’re talking about.”

The documentary, now in theaters, will air on PBS in May. Pack, who directed, wrote, and produced the documentary, has also created a dozen other documentaries that aired on public television. “I believe conservatives should try harder to get their films broadcast on PBS,” he says. “Millions of people see it.”

Tom Klingenstein, another donor to the film, says he hasn’t typically invested in documentaries, but he couldn’t pass up Created Equal. “I think he has a great story.” Klingenstein was impressed by the film’s focus on Thomas’s grandfather. “Without the grandfather, as I understand the story, Thomas wouldn’t be where he is. It speaks to the importance of parenting.”

Pack notes that philanthropy plays an important role in the production of documentary films, which generally cost from several hundred thousand to a few million dollars. Private foundation funding is especially crucial for projects heading to public television. He hopes his film will encourage more givers to invest in films.

Documentaries also need help after production is completed. Films can’t change the world unless they get viewed. Kim Dennis, president of the Searle Freedom Trust, says her group contributed $200,000 to help distribute and advertise Created Equal. “We were able to see a rough cut of the film, and knew how good it was, so we were delighted to be able to help them out with a grant for marketing,” she says.

Thanks to a handful of givers, our Supreme Court’s longest-tenured sitting Justice is speaking out in a way he never has before. Coming to a theater and PBS station near you.

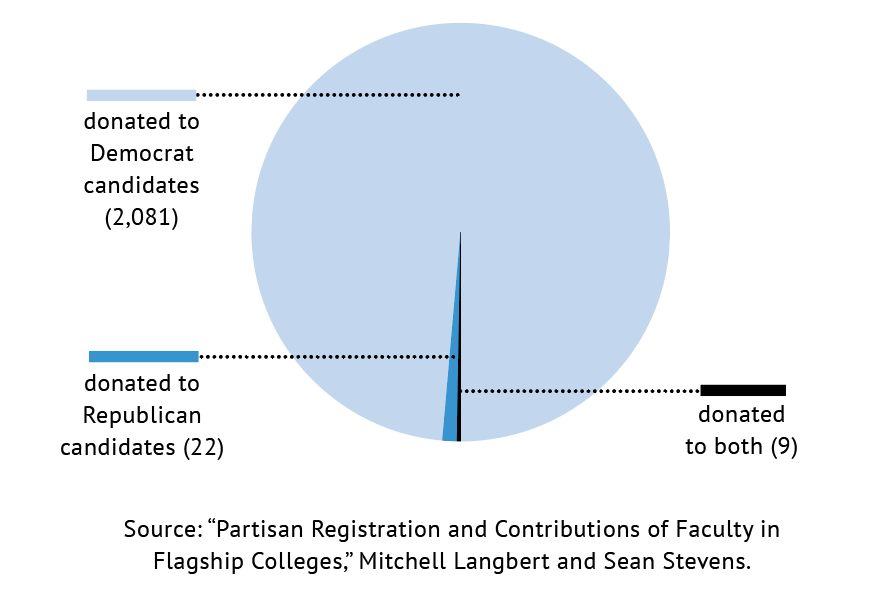

Donations by Professors: DONATIONS BY PROFESSORS: The National Association of Scholars has just published a study of recent political donations by thousands of professors at colleges and universities, as collated by the Federal Election Commission. The findings:

Send future leads for The Exchange to: editor@PhilanthropyRoundtable.org