From Philanthropy, Winter 2013, “American History’s Great Philanthropists”

John D. Rockefeller Jr.

In 1926, John D. Rockefeller Jr. visited Williamsburg, Virginia, then little more than the College of William and Mary surrounded by a few crumbling churches. Always something of a historical romantic, Rockefeller warmed to the idea of reviving the town, one building at a time, recapturing the lost world of the Old Dominion. He insisted on scrupulous historical accuracy—“no scholar must ever be able to come here and say we have made a mistake,” he often instructed his subordinates—and he immersed himself in antiquarian scholarship to ensure his own comfort with the work. In what ultimately became a nearly $60 million gift, he brought the colonial village back to life, even buying a manor house where he and his wife would spend two months every year. The entire project became a labor of love. “I really belong in Williamsburg,” he once said, wistfully.

Zachary Fisher

In the late 1970s, Zachary Fisher learned that the USS Intrepid, a storied aircraft carrier with service in the Pacific during World War II, as well as Korea and Vietnam, was scheduled to be retired and sold for scrap metal. Fisher hated the idea that the nation would “cut up our own history for razor blades.” He decided to acquire the Intrepid and convert it into a floating museum moored off the banks of Manhattan. It was a monumental undertaking. He put up the first $25 million. Then he shepherded along an act of Congress. (Since it was the first time an aircraft carrier had been sold to a private party, it required a federal statute to complete the transaction.) Next he battled the New York City building commission. (Lacking any precedent for an aircraft-carrier museum, the city inspectors originally treated the Intrepid as a multi-story skyscraper lying on its side.) Since it opened in 1982, the Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum has greeted more than 10 million visitors.

Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum

Robert H. Smith

Robert H. Smith made a fortune developing modern commercial buildings in the greater Washington metropolitan area, and dedicated much of that fortune to preserving historic sites near the nation’s capital. In the mid-1990s, he began funding the restoration of Montpelier, the bucolic plantation home of James Madison. In 2000, Smith took on another preservation project: Mount Vernon. Working closely with other donors, Smith helped greatly expand the educational content at George Washington’s historic home. He was similarly a major benefactor of Jefferson’s Monticello, Gettysburg National Military Park, and the New-York Historical Society. He took charge of restoring the Benjamin Franklin House in London, which opened on January 17, 2006—just in time for Ben’s 300th birthday. When Abraham Lincoln’s summer cottage in northern Washington, D.C., was re-opened to the public in February 2008, Smith was again the lead funder, contributing more to the project than the federal government. “I consider myself,” Smith said, “a grateful American.”

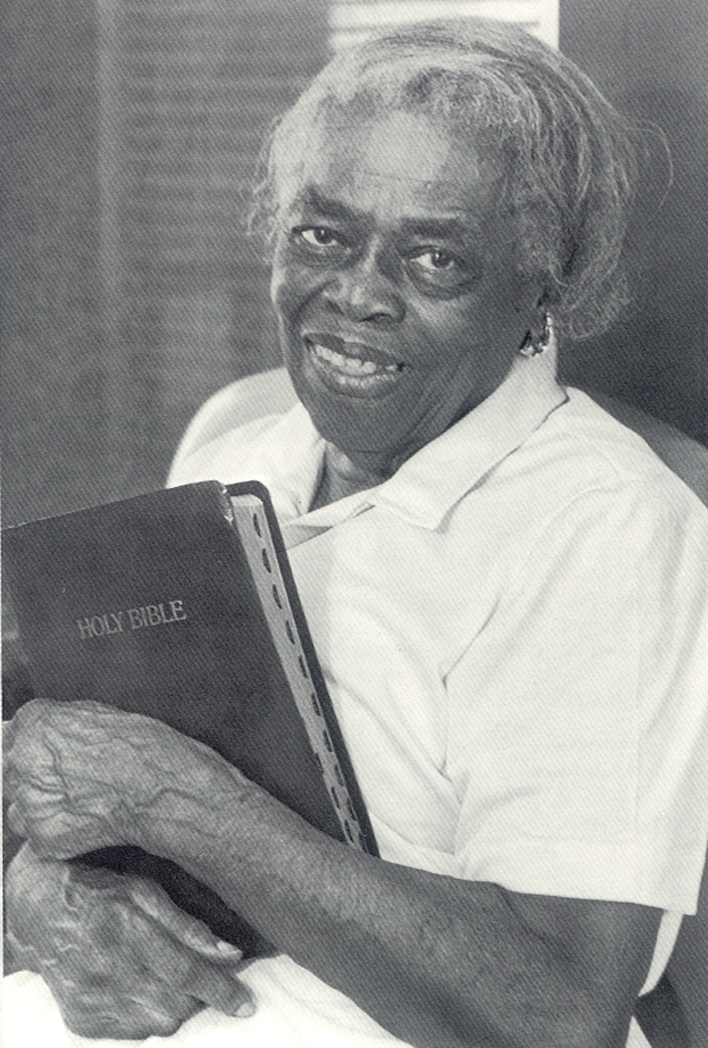

Oseola McCarty

Oseola McCarty was born into the world in 1908, and it was a raw start. She was conceived when her mother was raped on a wooded path in rural Mississippi as she returned from tending to a sick relative. Oseola was raised in Hattiesburg by her grandmother and aunt, who cleaned houses, cooked, and took in laundry. She dropped out of sixth grade to care for her aunt, taking up work as a washerwoman. She never returned to school.

McCarty scrubbed laundry by hand on a rub board. “Work became the great good of her life,” explained one person who knew her. McCarty herself put it this way: “I knew there were people who didn’t have to work as hard as I did, but it didn’t make me feel sad. I loved to work, and when you love to do anything, those things don’t bother you.”

She had a strong and virtuous character and good habits. She lived frugally, walking almost everywhere, including more than a mile to get her groceries. In addition to the dignity of work, McCarty’s satisfactions were the timeless ones: faith in God, family closeness, and love of locale.

These sturdy habits ran together to produce McCarty’s final secret. When she retired in 1995, her hands painfully swollen with arthritis, the washerwoman who had been paid in little piles of coins and dollar bills her entire life had $280,000 in the bank.

Setting aside just enough to live on, McCarty donated $150,000 to the University of Southern Mississippi to fund scholarships for worthy but needy students seeking the education she never had. When they found out what she had done, over 600 men and women in Hattiesburg and beyond made donations that more than tripled her original endowment. Today, the university presents several full-tuition McCarty scholarships every year.

Oseola McCarty deserves to be recognized not only for her own accomplishments, but as a representative of millions of other everyday Americans who give humbly of themselves, year after year. There are Oseolas all across the U.S.

Gifts like hers cumulate with millions of others from ordinary Americans in a powerful way. Sixty-five percent of U.S. households make charitable contributions every year, with the average household contribution being $2,213. That is three to seven times as much generosity as in equivalent Western European nations. In addition, half of all U.S. adults volunteer their time to charitable activities, totaling an estimated 20 billion hours every year.

The result: A massive charitable flow of more than $300 billion per year, with more than 80 percent coming from generous individuals. One may quite accurately say that it is Oseola McCarty and similar partners who make America the most generous nation on earth.