Brain surgery: The words alone invoke both awe and dread. A surgeon’s ability to expose and heal that sphere of mysteries is amazing and terrifying.

Now imagine brain surgery in rural Tanzania, a Cessna flight away from any major urban area, at a poorly equipped hospital, by a “doctor” who hasn’t gone to medical school. The idea sounds crazy, even doomed. But Tony Bartelme’s argument in A Surgeon in the Village is that this idea is not only plausible, it is the best way to build vital surgical capacity across Africa and much of the developing world.

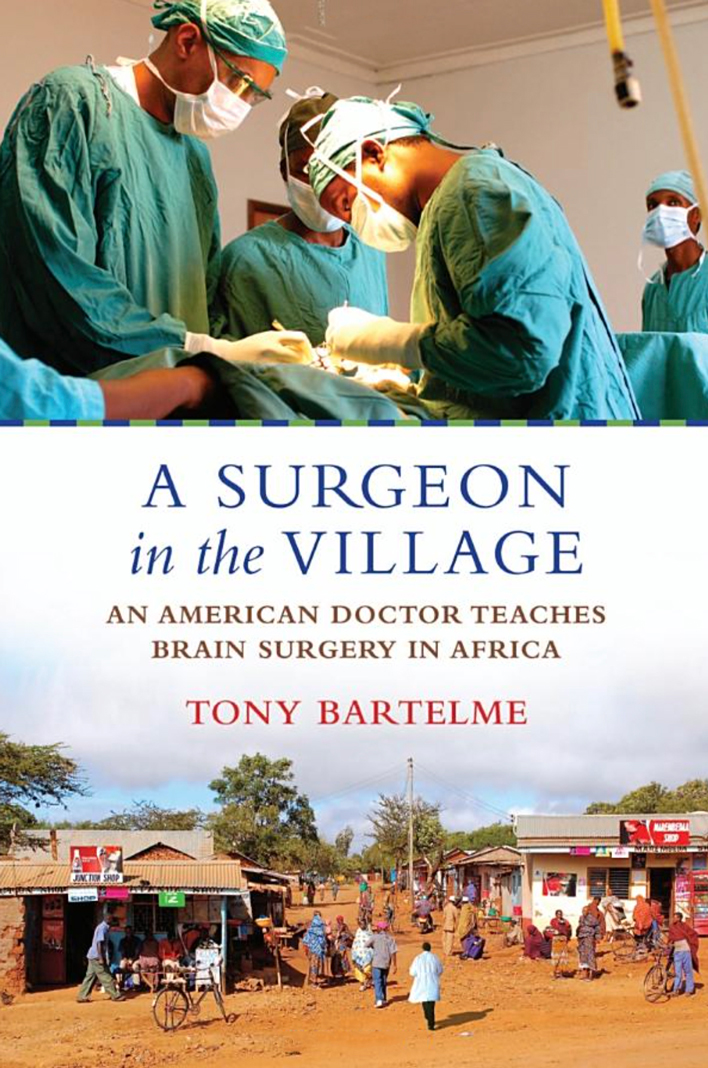

A Surgeon in the Village: An American Doctor Teaches Brain Surgery in Africa By Tony Bartelme

Bartelme’s book follows American neurosurgeon Dilan Ellegala as he sets out to solve a crisis of medical capacity in Tanzania. After nearly burning out in neurosurgical residency, Ellegala takes a sabbatical at the Haydom Lutheran Hospital in rural Tanzania, where he hopes to take a deep breath before returning to his high-intensity career track. Ellegala finds Haydom to be a bustling hub of health care—the only source of health care, really—for two million people.

In this swarm of activity Ellegala discovers two things that unsettle him: A crushing load of people who need basic brain surgery, and an ever-rotating cast of Western doctors who come in for short spurts. The permanent Tanzanian personnel work around the Western doctors, knowing that their latest saviors will be there only a few weeks. And Ellegala, with his medical-school debt and ambition, knows that he will be one of those leaving soon, too.

So instead of filling his time with surgeries, Ellegala takes another approach, which would become the central idea animating the organization he founds, Madaktari Africa. He selects a promising Tanzanian technician with a few years of formal medical training but no M.D. and teaches him to do basic brain surgery. The process, Bartelme shows, is quite similar to Ellegala’s own training in the United States, minus years and years of formal schooling: See (and touch) the brain, follow very specific procedures under close supervision, then do the procedures yourself.

Ellegala’s Tanzanian protégé is Emmanuel Mayegga, and he serves as the test case for Ellegala’s theory, which is that Western doctors can teach relatively complex procedures to capable Tanzanians and break their total dependence on a stream of short-term foreign volunteers. Mayegga isn’t perfect, but Ellegala wasn’t either while he was being trained. He once drilled too far into a patient’s skull and bore into the brain itself. And just as Ellegala built independence and confidence during his training, leading to stellar competence, Mayegga does the same, allowing him to continue to do lifesaving surgeries after his mentor returns to the U.S.

So Ellegala teaches Mayegga. And Mayegga teaches another, so that when he leaves to go to formal medical school, the surgeries continue. And this doctor trains another to do the same, and the surgeries still continue, without Western doctors present, with very respectable results. Lives are saved, and saved by Tanzanian hands. “Teach a man to fish is not enough,” Ellegala says. “Our job is to cultivate leaders to teach.”

Ellegala’s pioneering work reminds us that urgent global-health work isn’t limited to investing in preventable diseases. “A huge infrastructure had been created to combat malaria, AIDS, and tuberculosis—important work,” Bartelme writes. “But that didn’t help a mother who lost her child because no obstetrician was there to do a C-section, nor did it help the boy who became an invalid after a motorcycle accident because a trauma doctor wasn’t available to set his bones. Families who lost loved ones because of this dearth of doctors also lost trust in the hospital.”

Accidents that cause hemorrhaging on the brain are not uncommon, and when they happen, patients need surgery to release pressure and remove clots so they stay alive. This doesn’t necessarily require cutting-edge neurology. When a baby contracts hydrocephalus, a deadly condition where water builds up in the brain, surgical intervention is required. That doesn’t have to take place in a Western-style surgical theater.

While the need is expansive, the focus from major funders isn’t there, Bartelme contends. He quotes the founders of the international medical charity Partners In Health, Paul Farmer and Jim Kim: “Although disease treatable by surgery remains a ranking killer of the world’s poor, major financers of public health have shown that they do not regard surgical disease as a priority.”

Bartelme does not explore the reasons why major donors have mostly hewed tightly to infectious diseases like malaria, but it is not hard to imagine why. These diseases are huge killers, and the solutions are relatively simple and easily implemented. Training surgeons is personnel-intensive, requiring deep expertise, long-term maintenance of infrastructure, and enduring management capabilities that developing countries don’t have.

So Madaktari Africa has partnered with American teaching hospitals to bring Western medical expertise in a range of disciplines to promising African medical professionals. The deep relationships necessary for their teach-first model are best suited to smaller-scale initiatives. Ellegala is closely connected to the people at Haydom hospital, and has kept returning there to train up leaders. Intense mentoring is essential to the model he has developed, and that is hard to buy with large grants that can become faceless and bureaucratic.

Smaller initiatives can also be nimbler, allowing them to circumvent the blockages that bureaucracies can impose. Ellegala did not choose to teach M.D.s how to operate on the brain—there were no Tanzanian M.D.s at the hospital. He chose the person who showed the most potential. This ability to see past credentials and regulations to the person (who will be the key to success) is essential.

The example of Haydom also shows that certain basic medical infrastructure and supplies are a precondition for success. Ellegala could improvise the fashioning of some metal pieces into surgical tools, but if the hospital hadn’t had a C.T. scanner, any brain surgery would have been impossible. The hospital had one of three C.T. machines in the whole of Tanzania, which the Norwegian group Friends of Haydom bought for it. It costs money both to purchase technology and to service it when it breaks.

Ellegala’s teaching initiative tries to harness the benefits of short-term medical mission trips while mitigating the drawbacks. Very few Western doctors are able to live permanently in places like Haydom. Ellegala and his wife, a Dutch doctor whom he met in Haydom, love the hospital, but can’t move there forever. By sharing their expertise with local practitioners during these short-term trips, the expertise stays when they leave.

Dilan Ellegala’s vision of building up competent local doctors to do surgery is having a greater impact than he could have wrought by wielding his impressive skills on his own. He saw that he had something more fundamental than his technique to share—his knowledge. And he found that he could entrust it to the people he found in Tanzania.

Andrew Evans has worked as a consultant in Rwanda.