A town of dirt roads and 1,700 residents, Pearlington, Mississippi, is rarely seen, rarely heard from, rarely noted. Though the town sits at the mouth of the Pearl River, most passersby know it only as a blink on a two-lane highway taking them to New Orleans or some Gulf Coast retreat, a dot on the Mississippi- Louisiana state line.

Not brothers Chris and Robin Sorensen, though. The founders of the Firehouse Subs chain that now racks up $650 million in annual sales hold a special place in their hearts for Pearlington. In 2005, the Sorensen brothers spent three days there serving food and water to residents battered by Hurricane Katrina.

It was ground zero for Katrina’s wrath in the early morning hours of August 29, 2005. The town was consumed by a 30-foot storm surge and accompanying 140-mile-per-hour winds. The town’s elementary school, library, and post office were swallowed up, and all but a handful of the community’s 800 homes bludgeoned into wrecks.

From their homes in Jacksonville, Florida, the Sorensen brothers helplessly watched Hurricane Katrina’s destruction unfold on television. They felt compelled to do something, but didn’t know what until Robin heard Jacksonville fire chief Larry Peterson on the local radio. Peterson reported that about 100 local firefighters had traveled to Pascagoula, Mississippi, to assist in relief efforts, and he urged listeners to donate supplies. “If you take food to your local fire station, we’ll make sure it gets there,” Peterson said.

The Sorensen brothers, both former Jacksonville firefighters, called Peterson and soon hatched a plan to drive an 18-wheeler and bus packed with food and water to Pascagoula. “By the time we got there, though, the citizens of Jacksonville had given so much that there was actually excess,” Robin recalls.

A local police officer asked the brothers if their caravan might consider traveling to another town in need. Driving 75 miles to the west, they entered Pearlington—or what was left of it.

“When we got there, people were just walking around in a daze,” Chris remembers. “You looked in either direction and you just saw toothpicks.” Days after Katrina had made landfall in Pearlington, the tiny Mississippi town remained an overlooked casualty of the storm. Neither the U.S. government nor established disaster-relief charities had come to help. “There was no FEMA, no other responders,” Robin says. “Just us.”

As the brothers provided sustenance amid the wreckage, the residents’ spirits picked up. “Those folks still had a lot of work and uncertainty ahead of them,” Chris says, “but I hope we gave them some peace of mind and some sense that things would be okay, that better days were ahead.”

After leaving, the brothers traveled east through Mississippi’s southern edge, feeding students at a school in Kiln, hospital workers in Bay St. Louis, and military staff at an outpost in Waveland, where they swapped their remaining sandwiches for $2,000 worth of jet fuel to power their bus and rig back home. “I remember putting jet fuel in our diesel truck and thinking, ‘I really hope this works,’ ” Robin says.

The Sorensens returned to Jacksonville physically and emotionally spent, but also touched by the resilience of those they encountered. They would never be the same. The fraternal entrepreneurs, who had reinvented themselves once before, knew it was time for a new chapter in their lives.

The entrepreneurial itch

Helping people in danger comes naturally to Chris and Robin Sorensen. The brothers come from a long line of firefighters, and started their own careers as firemen. But they also felt an entrepreneurial itch, one they tried to scratch with failed ventures in video, real estate, and even a Christmas-tree farm.

Both men are avid cooks, and in the early 1990s they set their sights on running a restaurant. In the process of trying to take over a franchised sub shop, lightning struck. We can make better sandwiches than this, they decided, and do it on our own.

While Chris continued fighting fires to pay the bills, Robin got a job at another restaurant to learn the food-service business from the ground up. He made friends with the delivery guys and solicited their perspective and insights. He studied competitors.

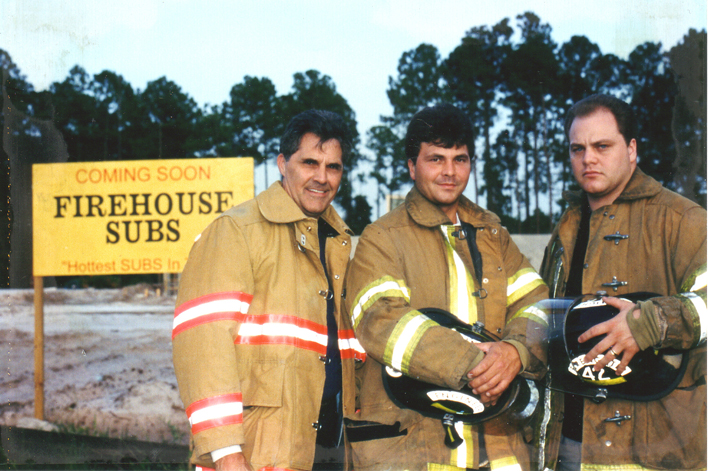

Two years later, with small loans and $16,000 on the credit card of Robin’s mother-in-law (which they hoped to keep secret from his father-in-law, who is an FBI agent), the brothers launched their first Firehouse Subs shop. From the 1994 get-go, guests flocked to their Jacksonville shop decorated with firefighting gear and memorabilia. They offered hearty portions and a unique steaming process for meats and cheeses that made their product distinctive.

“Customers loved the food, atmosphere, and customer service—and they kept coming back,” says Chris. Many patrons assumed the concept was a chain from another city. Instead it was an entirely independent creation of two hustling local siblings.

But soon there was indeed a chain being forged of new links. The Sorensens opened additional Jacksonville-area units, and began franchising. They ran a tight ship, maintaining financial discipline, choosing new franchise partners carefully, visiting all their stores regularly, and consistently working to perfect the restaurant experience—fussing over everything from sourcing new kitchen equipment to designing memorable packaging and dining rooms. Today, Firehouse Subs is a national brand with more than 1,000 restaurants.

The charitable impulse

Right from the opening of their first outlet, the Sorensens had raised money through various in-store initiatives for charities like the Muscular Dystrophy Association. They considered creating a formal nonprofit during the 1990s, but tabled those discussions to build on their existing relationship with MDA, out of uncertainty about how to build a charitable organization, establish a mission, and put time and money into it productively.

Their experience in post-Katrina Mississippi, however, motivated them to think more about philanthropy. “If there was ever a time to get something going, this was it,” Chris says. “We had been blessed with some good fortune, and needed to pass that along.”

The brothers began piecing together the core elements of a charitable strategy—causes that captured their attention, initiatives they could handle practically, with a reasonable chance of success. Quickly, their attention turned to first responders, a world they knew well. “Some public-safety organizations are lacking the tools they need to adequately serve their communities, so that’s the gap we decided to address,” Chris explains.

The brothers created the Firehouse Subs Public Safety Foundation. Their mission statement focused on enhancing the lifesaving capabilities of first responders. They secured 501c3 status and distributed acrylic boxes to each Firehouse Subs store for collecting spare change. Then they began taking grant requests.

“We didn’t set out with a business plan or a long-term vision,” Robin admits. “We just started with a sincere response and grassroots plans.”

The foundation’s very first donation—a used fire truck the brothers purchased on eBay—found a much-needed home in a special place: Pearlington, Mississippi. “I can’t tell you how good that felt,” Robin says.

Concentrating on disaster

A decade on, the Firehouse Subs Foundation has provided lifesaving equipment to first responders all across the U.S. It has also funded education to prevent disasters, training for disaster preparedness, relief supplies, and scholarships for trainees. This help so far exceeds $20 million.

About 80 percent of the foundation’s gifts go toward lifesaving equipment. More than 1,500 local public-safety organizations have received gear ranging from bulletproof vests to thermal imaging cameras to auto-crash extraction tools. The foundation has also donated automated external defibrillators, and rescue-ready all-terrain vehicles.

Organizations in need of equipment submit an online request, and each quarter the proposals are reviewed by the foundation’s seven-member board (which includes both Robin and Chris as well as retired and current first responders and financial professionals). Community needs and the background of applicants are investigated. Last year, the foundation approved about 400 grants, and negotiated with vendors to procure equipment at reasonable rates.

“We approve as many as we can,” Robin says. Each quarter, about a million and a half dollars is distributed. “Honestly, it’s the most fun we ever have.”

One recent grant provided three car and building extrication tools—a spreader, cutter, and ram—for the Wayne-Westland Fire Department near Detroit. Their existing extrication tools relied on a 20-year-old, pump-driven system that was not dependable. Fire captain Fred Gilstorff and others raised $17,000 from local businesses; the Firehouse Subs Foundation provided the remaining $10,000.

“The day we got the tools, we had a crew behind the firehouse receiving training when a call for an automobile rollover came out,” Gilstorff says. “We were able to extract that person safely from the vehicle in a fraction of the time it would’ve taken otherwise.”

The foundation gifted the Xenia Township Fire Department near Dayton, Ohio, with a $14,000 CPR machine. It delivers more consistent and efficient chest compressions than a human. Deputy fire chief Greg Beegle and colleagues submitted the request amidst growing research linking the quality of CPR to survival. “The device is a bridge to the hospital, which can take us some time to get to given that we cover nearly 80 square miles in a rural area,” says Beegle. The machine frees up a first responder to insert an artificial airway, start an intravenous line, or defibrillate while it provides cardio-pulmonary assistance.

Beegle reports his team used the machine in six cardiac-arrest cases within the first six months of receiving it. “To know we have a group looking out for us, advocating for us, and helping us do our best is incredibly inspiring,” he says.

When they receive reports like these, or learn that a foundation-supplied search dog found a woman with Alzheimer’s lost in the woods, the Firehouse Subs philanthropic team gets a thrill. “We want to put the best tools in the best hands, and never want to hear first responders say, ‘If only we had this or that,’ ” says executive director Robin Peters.

One task, many tools

In addition to providing equipment to first responders, the Firehouse Subs Foundation supports partners who provide the public with DUI education, fire detectors, and information on carbon-monoxide poisoning. It assists victims and public-safety workers through partners like the American Red Cross. It funds academic scholarships for individuals pursuing careers in public safety. And it provides quality-of-life aids for first responders and military veterans injured in the line of duty.

The foundation also mobilizes vendors in the Firehouse Subs supply chain to deliver food and water after disasters. This combination of nonprofit and for-profit tools helped feed thousands following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the 2011 tornadoes in Alabama, and the 2016 floods in West Virginia. “We have an amazing ability to react quickly because we have the infrastructure of a 1,000-unit restaurant company behind us,” notes Peters.

She reports that 70 percent of the foundation’s $8 million in 2015 revenue came directly from Firehouse Subs outlets. In addition to placing donation canisters at register counters, restaurants sell leftover five-gallon pickle buckets for a $2 contribution, and promote a program that allows guests to round their bill up to the nearest dollar to benefit the foundation. “With 1,000 restaurants, that’s a big revenue stream for us,” Peters says.

The remainder of its funding comes from an annual appeal, charitable golf and tennis tournaments, and executive donations. The Sorensens remain the organization’s largest individual donors, including a $1 million gift last year. The brothers often time their donations to strategic points when they can stimulate other giving, like offering a matching challenge at the annual business meeting for Firehouse Sub franchisees.

The foundation mobilizes vendors in the Firehouse Subs supply chain to deliver food and water after disasters. This combo of nonprofit and for-profit tools has fed thousands.

Peters calls Robin and Chris the foundation’s most devout champions and says anything she asks of them, they provide. The foundation enjoys rent-free offices at the restaurant’s corporate headquarters in Jacksonville and access to professional expertise in areas like marketing and accounting. As a result, 90 cents from every dollar the foundation receives goes directly to programming. “We’re not paying for many of the services that other nonprofits do, and that really allows us to put our fundraising dollars to work,” Peters says.

The Firehouse Subs brand benefits from good feelings generated by this philanthropy. The brothers insist, though, that any corporate burnishing is secondary to their direct charitable aspirations. “This was never a big, strategic marketing initiative, because we’re not that smart,” Robin quips. “This all starts from the heart.”

“Not a day goes by that we don’t focus on growing our foundation,” adds Chris. In fact, having transferred day-to-day leadership of the company to others (“we surrounded ourselves with people who can do the job better than we can,” says Robin), the brothers now devote most of their time and energy to the foundation. In their own balance between corporate and charitable interests, the tail is now wagging the dog.

“From the beginning,” exudes Robin, “we really believed the foundation could do great things. To see where it is today, the people it’s helped, is immensely satisfying. And that just motivates us even more.”

If you’re itching to try the food, read a review of the sandwiches here.